Welcome Home Brother Charles (1975)

- Matt Rotman

- Feb 13, 2019

- 3 min read

After a brief hiatus shooting my short film, I’m back. And for the occasion, I’ve brought with me Welcome Home Brother Charles, Jamaa Fanaka’s pissed off, socially conscious revenge film about a wronged man’s pursuit of street justice with his…magical penis?

Also known as Soul Vengeance, Welcome Home Brother Charles (1975) is the debut feature film from Fanaka, then still a film student at UCLA. The director is most known for his later Penitentiary trilogy, but before all that, he pumped out some of the most unusual entries in the blaxploitation cycle—Brother Charles a major case in point.

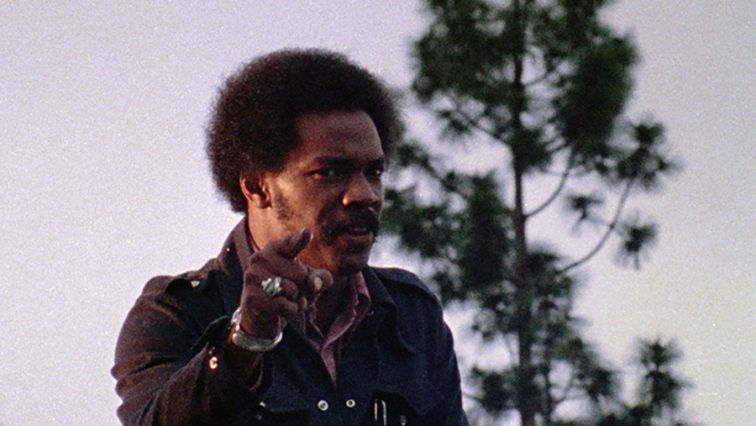

Like most films of the revenge ilk, the plot is simple enough. Charles (Marlo Monte) and N.D. (Jake Carter) are two small time drug pushers being surveilled by a nasty, racist piece of shit of a cop. Noticing the heat, the two make a run for it, and Charles is arrested, while N.D. gets away. Charles is brutally assaulted by the cop, to the point where the cop even tries to castrate him. None of this makes it into trial, of course, and Charles is framed for a crime he didn’t commit and sent away for three years.

The film picks up on the day Charles is released. He’s a changed man, wanting only to go straight. However, he’s pushed to the limit by the environment he’s dropped into. N.D. is now a local crime boss who stole Charles’ girlfriend. He’s roughed up by N.D.’s goons. He can’t get a job because of his felon status. He watches on TV as the cop who framed him becomes a local hero. A man can only get pushed so far.

Thus, Charles sets out on a path of vengeance that has to be seen to be believed.

It’s quite astounding how fully formed Fanaka is as a filmmaker right out of the gate. Sure, the film is cheap and amateurish, but the direction, pacing, and presentation of ideas is as assured as from someone who had been making films for a decade. There’s a tight balancing act that Brother Charles walks between pissed off political commentary, sleazy exploitation, drama, horror, and the celebration of Compton culture.

And in that way, the obvious blaxploitation label makes me a little uncomfortable (I know Fanaka didn’t like his films having that moniker). This is more of a student art film that uses its more exploitive elements as a surreal form of storytelling—and, well, who are we kidding?—to help get distribution in the grindhouse theaters at the height of the blaxploitation cycle.

Let’s also not miss the forest for the trees here: for as gonzo batshit as Brother Charles becomes in its final third, it’s a beautiful, tragic film. After Charles is released and walking the streets, Fanaka takes a very documentarian-like approach to shooting the streets of Compton. We see every bit of the grimy life that is created by the structural racism that segregates and denigrates the populace of South Central. Yet, as much as it is social commentary, it’s a love letter to the culture there. There’s a particularly wonderful sequence where after showing a blues guitar player, we cut to a drunk guy smiling and dancing on the street. It would appear to be a direct reference to Langston Hughes’ description of the blues, “laughing to keep from crying.”

The film is also smart enough take the revenge element to its fullest conclusion: the complete and utter perdition of the soul caused by the pure, consumption of hate. Charles, as played by Monte, is an extremely likeable character. We hate watching his acts of violence, and we wait with dread for his inevitable self-destruction.

Welcome Home Brother Charles gets most of its cult cachet from the magical penis element (which I won’t spoil here), but that overshadows the political point of that plot device, which is a sardonic, satirical take on white male sexual anxiety toward African Americans. I mean, c’mon, the film opens with credits playing over an African male fertility statue with a large, erect dick; a lot of the drama in the movie stems from the white men in power feeling sexually insecure with their wives—the magical penis stuff just serves to hammer this theme home.

Though rough around the edges, Fanaka’s debut deserves more love. Hopefully the Vinegar Syndrome Blu-ray (which includes the director’s second film, Emma Mae) will put it into the consciousness of people who would otherwise not even know of its existence. Required viewing as far as I’m concerned.

Comments